Out-of-place Artifact on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An out-of-place artifact (OOPArt or oopart) is an artifact of historical, archaeological, or paleontological interest found in an unusual context, which challenges conventional historical chronology by its presence in that context. Such artifacts may appear too advanced for the technology known to have existed at the time, or may suggest human presence at a time before humans are known to have existed. Other examples may suggest contact between different cultures that is hard to account for with conventional historical understanding.

This description of archaelogical objects is used in

An out-of-place artifact (OOPArt or oopart) is an artifact of historical, archaeological, or paleontological interest found in an unusual context, which challenges conventional historical chronology by its presence in that context. Such artifacts may appear too advanced for the technology known to have existed at the time, or may suggest human presence at a time before humans are known to have existed. Other examples may suggest contact between different cultures that is hard to account for with conventional historical understanding.

This description of archaelogical objects is used in

''The Coso Artifact Mystery from the Depths of Time?''

, Reports of the National Center for Science Education. 24(2):26–30 (March/April 2004) Retrieved March 8, 2014. Claimed OOPArts have been used to support religious descriptions of

* The Shroud of Turin contains an image that resembles a sepia photographic negative. It is much clearer when it is converted to a positive image. The actual method that resulted in this image has not yet been conclusively identified. Some claim the image depicts Jesus of Nazareth and the fabric is the

* The Shroud of Turin contains an image that resembles a sepia photographic negative. It is much clearer when it is converted to a positive image. The actual method that resulted in this image has not yet been conclusively identified. Some claim the image depicts Jesus of Nazareth and the fabric is the  * The

* The

*

*

''Archaeologists Revisit Iraq.'' interview with Elizabeth Stone

Talk of the Nation, National Public Radio. Washington, DC. The "battery" strongly resembles another type of object with a known purpose – storage vessels for sacred scrolls from nearby

''Metallic vase from Dorchester, Massachusetts.''Bad Archaeology.

/ref> *

''The Mystery Stone''.

New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord, New Hampshire.

''New England's 'Mystery Stone': New Hampshire Displays Unexplained Artifact 134 Years Later.''

Associated Press. Retrieved March 8, 2014. * ''

''Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca.''

Dept. of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico.Schaaf, P and GA Wagner (1991) ''Comments on 'Mesoamerican Evidence of Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Contacts,' by Hristov and Genovés.'' Ancient Mesoamerica. 10:207–213.

* Abydos helicopter: A

* Abydos helicopter: A

TalkOrigins. Retrieved 4 May 2019. * Newark Holy Stones: Used as extremely unlikely evidence that

An out-of-place artifact (OOPArt or oopart) is an artifact of historical, archaeological, or paleontological interest found in an unusual context, which challenges conventional historical chronology by its presence in that context. Such artifacts may appear too advanced for the technology known to have existed at the time, or may suggest human presence at a time before humans are known to have existed. Other examples may suggest contact between different cultures that is hard to account for with conventional historical understanding.

This description of archaelogical objects is used in

An out-of-place artifact (OOPArt or oopart) is an artifact of historical, archaeological, or paleontological interest found in an unusual context, which challenges conventional historical chronology by its presence in that context. Such artifacts may appear too advanced for the technology known to have existed at the time, or may suggest human presence at a time before humans are known to have existed. Other examples may suggest contact between different cultures that is hard to account for with conventional historical understanding.

This description of archaelogical objects is used in fringe science

Fringe science refers to ideas whose attributes include being highly speculative or relying on premises already refuted. Fringe science theories are often advanced by persons who have no traditional academic science background, or by researchers ...

such as cryptozoology

Cryptozoology is a pseudoscience and subculture that searches for and studies unknown, legendary, or extinct animals whose present existence is disputed or unsubstantiated, particularly those popular in folklore, such as Bigfoot, the Loch Ness ...

, as well as by proponents of ancient astronaut

Ancient astronauts (or ancient aliens) refers to a pseudoscientific hypothesis which holds that intelligent extraterrestrial beings visited Earth and made contact with humans in antiquity and prehistoric times. Proponents suggest that this ...

theories, young Earth creationists

Young Earth creationism (YEC) is a form of creationism which holds as a central tenet that the Earth and its lifeforms were created by supernatural acts of the Abrahamic God between approximately 6,000 and 10,000 years ago. In its most widesp ...

, and paranormal

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding. Not ...

enthusiasts. It can describe a wide variety of items, from anomalies studied by mainstream science to pseudoarchaeology

Pseudoarchaeology—also known as alternative archaeology, fringe archaeology, fantastic archaeology, cult archaeology, and spooky archaeology—is the interpretation of the past from outside the archaeological science community, which rejects ...

to objects that have been shown to be hoaxes or to have mundane explanations.

Critics argue that most purported OOPArts which are not hoaxes are the result of mistaken interpretation and wishful thinking, such as a mistaken belief that a particular culture could not have created an artifact or technology due to a lack of knowledge or materials. In some cases, the uncertainty results from inaccurate descriptions. For example, the cuboid Wolfsegg Iron

The Wolfsegg Iron, also known as the Salzburg Cube, is a small cuboid mass of iron that was found buried in Tertiary lignite in Wolfsegg am Hausruck, Austria, in 1885. It weighs 785 grams (1 lb 12 oz) and measures (2¾" x 2¾" x 1¾"). F ...

is not really a perfect cube, nor are the Klerksdorp sphere

Klerksdorp spheres are small objects, often spherical to disc-shaped, that have been collected by miners and rockhounds from 3-billion-year-old pyrophyllite deposits mined by Wonderstone Ltd., near Ottosdal, South Africa. They have been cited by ...

s actual perfect spheres. The Iron pillar of Delhi

The iron pillar of Delhi is a structure high with a diameter that was constructed by Chandragupta II (reigned c. 375–415 AD), and now stands in the Qutb complex at Mehrauli in Delhi, India.Finbarr Barry Flood, 2003"Pillar, palimpsets, and pr ...

was said to be "rust proof", but it has some rust near its base; its relative resistance to corrosion is due to slag inclusions left over from the manufacturing conditions and environmental factors.

Supporters regard OOPArts as evidence that mainstream science is overlooking huge areas of knowledge, either willfully or through ignorance. Many writers or researchers who question conventional views of human history have used purported OOPArts in attempts to bolster their arguments. Creation science

Creation science or scientific creationism is a pseudoscientific form of Young Earth creationism which claims to offer scientific arguments for certain literalist and inerrantist interpretations of the Bible. It is often presented without ove ...

often relies on allegedly anomalous finds in the archaeological record to challenge scientific chronologies and models of human evolution.Stromberg, P, and PV Heinrich (2004''The Coso Artifact Mystery from the Depths of Time?''

, Reports of the National Center for Science Education. 24(2):26–30 (March/April 2004) Retrieved March 8, 2014. Claimed OOPArts have been used to support religious descriptions of

prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

, ancient astronaut theories, and the notion of vanished civilizations that possessed knowledge or technology more advanced than that known in modern times.

Unusual artifacts

*Antikythera mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism ( ) is an Ancient Greek hand-powered orrery, described as the oldest example of an analogue computer used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses decades in advance. It could also be used to track the four-yea ...

: A form of mechanical computer

A mechanical computer is a computer built from mechanical components such as levers and gears rather than electronic components. The most common examples are adding machines and mechanical counters, which use the turning of gears to increment out ...

created between 150 and 100 BC based on theories of astronomy and mathematics believed to have been developed by the ancient Greeks. Its design and workmanship reflect a previously unknown, but not implausible, degree of sophistication and engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad range of more speciali ...

.

* Maine penny

The Maine penny, also referred to as the Goddard coin, is a Norwegian silver coin dating to the reign of Olaf Kyrre King of Norway (1067–1093 AD). It was claimed to be discovered in Maine in 1957, and it has been suggested as evidence of P ...

: An 11th-century Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

coin found in a Native American shell midden at the Goddard Site

The Goddard Site is a prehistoric archaeological site in Brooklin, Maine. The site is notable for the large number of stone artifacts found, most of which were sourced at locations well removed from the area, and for the presence of worked copper ...

in Brooklin, Maine

Brooklin is a town in Hancock County, Maine, United States. The population was 827 at the 2020 census.

History

Brooklin was originally part the larger town of Sedgwick. Brooklin broke off and formed its own town in 1849. A few weeks later, ...

, United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, which some authors have argued is evidence of direct contact between Vikings and Native Americans in Maine. The coin need not imply actual exploration of Maine by the Vikings, however; mainstream belief is that it was brought to Maine from Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

or Newfoundland (where Vikings are known to have established colonies as early as the late 10th century) via an extensive northern trade network operated by indigenous peoples. If Vikings did indeed visit Maine, a much greater number and variety of Viking artifacts might be expected in the archaeological record there. Of the nearly 20,000 objects found over a 15-year period at the Goddard Site, the coin was the sole non-native artifact.

burial shroud

Shroud usually refers to an item, such as a cloth, that covers or protects some other object. The term is most often used in reference to ''burial sheets'', mound shroud, grave clothes, winding-cloths or winding-sheets, such as the famous Shr ...

in which he was wrapped after crucifixion. Mention of the shroud first appeared in historical records in 1357. In 1988, radiocarbon dating established that the shroud was from the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, between the years 1260 and 1390.Taylor, R.E. and Bar-Yosef, Ofer. ''Radiocarbon Dating, Second Edition: An Archaeological Perspective''. Left Coast Press, 2014, p. 165. All hypotheses put forward to challenge the radiocarbon dating have been scientifically refuted,Radiocarbon Dating, Second Edition: An Archaeological Perspective, By R.E. Taylor, Ofer Bar-Yosef, Routledge 2016; pp. 167–168. including the medieval repair hypothesis,R. A. Freer-Waters, A. J. T. Jull, "Investigating a Dated piece of the Shroud of Turin", ''Radiocarbon'' 52, 2010, pp. 1521–1527.The Shroud, by Ian Wilson; Random House, 2010, pp. 130–131. the bio-contamination hypothesis and the carbon monoxide hypothesis.Professor Christopher Ramsey, Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, Oxford University, March 2008, at https://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/shroud.html

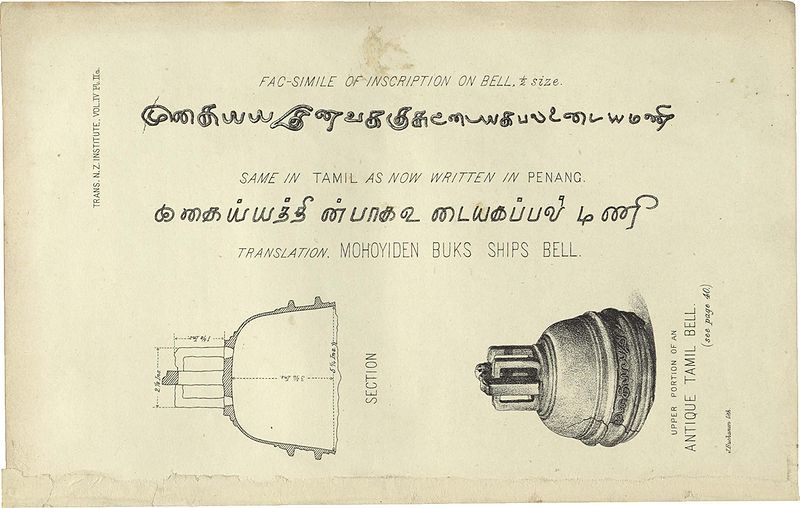

Tamil Bell

__NOTOC__

The Tamil Bell is a broken bronze bell discovered in approximately 1836 by missionary William Colenso. It was being used as a pot to boil potatoes by Māori women near Whangarei in the Northland Region of New Zealand.

The bell is 1 ...

is a broken bronze bell with an inscription of old Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

* Tamils, an ethnic group native to India and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka also called ilankai tamils

**Tamil Malaysians, Tamil people native to Malaysia

* Tamil language, nativ ...

. The bell is a mystery due to its discovery in New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

by a missionary. Although nobody knows for certain how the bell came to New Zealand, one possible theory is that it was dropped off by Portuguese sailors who had acquired it from Tamil traders. Prior to being discovered by the missionary, local Maori had used it as a cooking pot. Given that it was supposedly discovered generations earlier, the artifact's exact origins could not be identified. The bell is now located at the National Museum of New Zealand

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is New Zealand's national museum and is located in Wellington. ''Te Papa Tongarewa'' translates literally to "container of treasures" or in full "container of treasured things and people that spring f ...

.

Questionable interpretations

*

* Baghdad Battery

The Baghdad Battery is the name given to a set of three artifacts which were found together: a ceramic pot, a tube of copper, and a rod of iron. It was discovered in present-day Khujut Rabu, Iraq in 1936, close to the metropolis of Ctesiphon, the ...

: A ceramic vase, a copper tube, and an iron rod made in Parthia

Parthia ( peo, 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 ''Parθava''; xpr, 𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅 ''Parθaw''; pal, 𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥 ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Med ...

n or Sassanid Persia

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

. Fringe theorists have hypothesized that it may have been used as a galvanic cell

A galvanic cell or voltaic cell, named after the scientists Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta, respectively, is an electrochemical cell in which an electric current is generated from spontaneous Oxidation-Reduction reactions. A common apparatus ...

for electroplating, though no electroplated artifacts from this era have been found.Von Handorf, DE, and DE Crotty (2002) ''The Baghdad battery – myth or reality?'' Plating and Surface Finishing. vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 84–87.Flatow, I (2012''Archaeologists Revisit Iraq.'' interview with Elizabeth Stone

Talk of the Nation, National Public Radio. Washington, DC. The "battery" strongly resembles another type of object with a known purpose – storage vessels for sacred scrolls from nearby

Seleucia on the Tigris

Seleucia (; grc-gre, Σελεύκεια), also known as or , was a major Mesopotamian city of the Seleucid empire. It stood on the west bank of the Tigris River, within the present-day Baghdad Governorate in Iraq.

Name

Seleucia ( grc-gre, Σ ...

.

* Dorchester Pot: A metal pot claimed to have been blasted out of solid rock in 1852. Mainstream commentators identify it as a Victorian-era candlestick or pipe holder.Steiger, B. (1979) ''Worlds Before Our Own.'' New York, New York, Berkley Publishing Group. 236 pp. Fitzpatrick-Matthews, K, and J Doeser (2007''Metallic vase from Dorchester, Massachusetts.''

/ref> *

Kensington Runestone

The Kensington Runestone is a slab of greywacke stone covered in runes

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with so ...

: A runestone

A runestone is typically a raised stone with a runic inscription, but the term can also be applied to inscriptions on boulders and on bedrock. The tradition began in the 4th century and lasted into the 12th century, but most of the runestones d ...

unearthed in 1898 in Kensington, Minnesota, entangled in the roots of a tree. Runologists have dismissed the inscription's authenticity on linguistic evidence, while geologists disagree as to whether the stone shows weathering that would indicate a medieval date.

* Kingoodie artifact: An object resembling a corroded nail, said to have been encased in solid rock. It was handled a number of times before being reported and there are no photographs of it.Sir David, B (1854) ''Queries and Statements concerning a Nail found imbedded in a Block of Sandstone obtained from Kingoodie (Mylnfield) Quarry, North Britain.'' Report of the Fourteenth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science vol. 51, John Murray London.

* Lake Winnipesaukee mystery stone: Originally thought to be a record of a treaty between tribes, subsequent analysis has called its authenticity into question.anonymous (nd''The Mystery Stone''.

New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord, New Hampshire.

''New England's 'Mystery Stone': New Hampshire Displays Unexplained Artifact 134 Years Later.''

Associated Press. Retrieved March 8, 2014. * ''

Sivatherium

''Sivatherium'' ("Shiva's beast", from Shiva and ''therium'', Latinized form of Ancient Greek θηρίον -'' thēríon'') is an extinct genus of giraffids that ranged throughout Africa to the Indian subcontinent. The species ''Sivatherium giga ...

'' of Kish

Kish may refer to:

Geography

* Gishi, Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan, a village also called Kish

* Kiş, Shaki, Azerbaijan, a village and municipality also spelled Kish

* Kish Island, an Iranian island and a city in the Persian Gulf

* Kish, Iran, ...

: An ornamental war chariot

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000 ...

figurine discovered in the Sumerian ruins of Kish, in what is now central Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

, in 1928. The figurine, dated to the Early Dynastic I period (2800–2750 BCE), depicts a quadrupedal mammal with branched horns, a nose ring, and a rope tied to the ring. Because of the shape of the horns, Edwin Colbert

Edwin Harris "Ned" Colbert (September 28, 1905 – November 15, 2001)O'Connor, Anahad ''The New York Times'', November 25, 2001. was a distinguished American vertebrate paleontologist and prolific researcher and author.

Born in Clarinda, Iowa, he ...

identified it in 1936 as a depiction of a late-surviving, possibly domesticated ''Sivatherium'', a vaguely moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult ma ...

-like relative of the giraffe that lived in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

but was believed to have become extinct early in the Holocene extinction event

The Holocene extinction, or Anthropocene extinction, is the ongoing extinction event during the Holocene epoch. The extinctions span numerous families of bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, ...

. Henry Field and Berthold Laufer

Berthold Laufer (October 11, 1874 – September 13, 1934) was a German anthropologist and historical geographer with an expertise in East Asian languages. The American Museum of Natural History calls him, "one of the most distinguished sinologi ...

instead argued that it represented a captive Persian fallow deer

The Persian fallow deer (''Dama mesopotamica'') is a deer species once native to all of the Middle East, but currently only living in Iran and Israel. It was reintroduced in Israel. It has been listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List since 200 ...

and that the antlers had broken over the years. The missing antlers were found in the Field Museum's storeroom in 1977. After restoration in 1985, it was conclusively identified as a depiction of a Caspian red deer

The Caspian red deer (''Cervus elaphus maral''), is one of the easternmost subspecies of red deer that is native to areas between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea such as Crimea, Asia Minor, the Caucasus Mountains region bordering Europe and Asia, ...

(''Cervus elaphus maral'').

* Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca head: A terracotta

Terracotta, terra cotta, or terra-cotta (; ; ), in its material sense as an earthenware substrate, is a clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic where the fired body is porous.

In applied art, craft, construction, and architecture, terracotta ...

offering head seemingly of Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

appearance found beneath three intact floors of a burial site in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and dated between 1476 and 1510. There are disputed claims that its dating is older. Ancient Roman or Norse provenance has not been excluded.Hristov, RH, and S. Genoves (2001''Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca.''

Dept. of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico.Schaaf, P and GA Wagner (1991) ''Comments on 'Mesoamerican Evidence of Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Contacts,' by Hristov and Genovés.'' Ancient Mesoamerica. 10:207–213.

Alternative interpretations

pareidolia

Pareidolia (; ) is the tendency for perception to impose a meaningful interpretation on a nebulous stimulus, usually visual, so that one sees an object, pattern, or meaning where there is none.

Common examples are perceived images of animals, ...

based on palimpsest

In textual studies, a palimpsest () is a manuscript page, either from a scroll or a book, from which the text has been scraped or washed off so that the page can be reused for another document. Parchment was made of lamb, calf, or kid skin an ...

carving in an ancient Egyptian temple.

* Dendera Lamps: Supposed to depict light bulbs, but made in Ptolemaic Egypt, debunked by the anlysis of the epigraphic text.

* : a disc made with incredible precision in very ancient times from Saqqara

Saqqara ( ar, سقارة, ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis ...

. Its purpose is unknown.

* Iron Man ( Eiserner Mann): An old iron pillar, said to be a unique oddity in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, but consistent with medieval methods of ironworking.

* Iron pillar of Delhi

The iron pillar of Delhi is a structure high with a diameter that was constructed by Chandragupta II (reigned c. 375–415 AD), and now stands in the Qutb complex at Mehrauli in Delhi, India.Finbarr Barry Flood, 2003"Pillar, palimpsets, and pr ...

: A "rust-proof" iron pillar which supposedly demonstrates more advanced metallurgy than was available in India before 1000 CE.

* London Hammer

The London Hammer (also known as the "London Artifact") is a name given to a hammer made of iron and wood that was found in London, Texas in 1936. Part of the hammer is embedded in a limey rock concretion, leading to it being regarded by some as a ...

: Also known as the "London Artifact", a hammer made of iron and wood that was found in London, Texas

London is an unincorporated community in northeast Kimble County, Texas, United States. According to the ''Handbook of Texas'', the community had an estimated population of 180 in 2000.

History

Len L. Lewis, a horse trader and former Union Army ...

, in 1936. Part of the hammer is embedded in a limy rock concretion.

* Meister Print: A supposed human footprint from the Cambrian period, long before humans existed, which has been debunked as the result of a natural geologic process known as spall formation."The "Meister Print" An Alleged Human Sandal Print from Utah"TalkOrigins. Retrieved 4 May 2019. * Newark Holy Stones: Used as extremely unlikely evidence that

Hebrew people

The terms ''Hebrews'' (Hebrew: / , Modern: ' / ', Tiberian: ' / '; ISO 259-3: ' / ') and ''Hebrew people'' are mostly considered synonymous with the Semitic-speaking Israelites, especially in the pre-monarchic period when they were still n ...

s lived in the Americas, but more probably a hoax.

* Pacal's sarcophagus lid: Described by Erich von Däniken

Erich Anton Paul von Däniken (; ; born 14 April 1935) is a Swiss author of several books which make claims about extraterrestrial influences on early human culture, including the best-selling ''Chariots of the Gods?'', published in 1968. Von D ...

as a depiction of a spaceship.

* Piri Reis map

The Piri Reis map is a world map compiled in 1513 by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis. Approximately one third of the map survives; it shows the western coasts of Europe and North Africa and the coast of Brazil with reasonable accu ...

: Several authors, and others such as Gavin Menzies

Rowan Gavin Paton Menzies (14 August 1937 – 12 April 2020) was a British submarine lieutenant-commander who authored books claiming that the Chinese sailed to America before Columbus. Historians have rejected Menzies' theories and assertions ...

and Charles Hapgood

Charles Hutchins Hapgood (May 17, 1904 – December 21, 1982) was an American college professor and author who became one of the best known advocates of the pseudo-scientific claim of a rapid and recent pole shift with catastrophic results.

Biogr ...

, have suggested that this map, compiled by the Turkish admiral Piri Reis

Ahmet Muhiddin Piri ( 1465 – 1553), better known as Piri Reis ( tr, Pîrî Reis or ''Hacı Ahmet Muhittin Pîrî Bey''), was a navigator, geographer and cartographer. He is primarily known today for his maps and charts collected in his ''Kita ...

, shows Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

long before it was discovered (cf. Terra Australis

(Latin: '"Southern Land'") was a hypothetical continent first posited in antiquity and which appeared on maps between the 15th and 18th centuries. Its existence was not based on any survey or direct observation, but rather on the idea that ...

).

* Quimbaya airplanes: Golden objects found in Colombia and made by the Quimbaya civilization

The Quimbaya (/kɪmbaɪa/) were a small indigenous group in present-day Colombia noted for their gold work characterized by technical accuracy and detailed designs. The majority of the gold work is made in '' tumbaga'' alloy, with 30% copper, ...

, which have been alleged to represent modern airplanes. In the Gold Museum, Bogotá

The Museum of Gold ( es, El Museo del Oro) is a museum located in Bogotá, Colombia. It is one of the most visited touristic highlights in the country. The museum receives around 500,000 tourists per year.Saqqara Bird: Supposedly depicts a glider, but made in Ancient Egypt.

* Shakōkidogū: Small humanoid and animal

Critical perspective on Creationist and New Age claims related to out-of-place artifacts

at Bad Archaeology

''Archaeology from the dark side''

at

Out-of-place artifacts article

at Bad Archaeology Forteana Pseudoarchaeology

figurine

A figurine (a diminutive form of the word ''figure'') or statuette is a small, three-dimensional sculpture that represents a human, deity or animal, or, in practice, a pair or small group of them. Figurines have been made in many media, with clay ...

s made during the late Jōmon period (14,000–400 BCE) of prehistoric Japan, said to resemble extraterrestrial astronauts.

* Stone spheres of Costa Rica

The stone spheres of Costa Rica are an assortment of over 300 petrospheres in Costa Rica, on the Diquís Delta and on Isla del Caño. Locally, they are also known as bolas de piedra (literally stone balls). The spheres are commonly attributed t ...

: Inaccurately described as being perfectly spherical, and therefore demonstrating greater stone-working skill in pre-Columbian times than has previously been known.

See also

* Ancient technology *Lost inventions

This is a list of lost inventions.

Lost inventions

* Artificial petrifaction of human cadavers invented by Girolamo Segato

* Greek fire

* ''Panjagan''

* Teleforce, Tesla's so-called death ray

Questionable examples

* Archimedes' heat ray

* A ...

* Anachronism

* Lazarus taxon

In paleontology, a Lazarus taxon (plural ''taxa'') is a taxon that disappears for one or more periods from the fossil record, only to appear again later. Likewise in conservation biology and ecology, it can refer to species or populations tha ...

– when a biological lineage is discovered to have been alive long after it was assumed extinct

* Geofact

A geofact (a portmanteau of ''geology'' and ''artifact'') is a natural stone formation that is difficult to distinguish from a man-made artifact. Geofacts could be fluvially reworked and be misinterpreted as an artifact, especially when compared ...

– Geological artifacts that look like man-made ones

Authors and works

*Charles Fort

Charles Hoy Fort (August 6, 1874 – May 3, 1932) was an American writer and researcher who specialized in anomalous phenomena. The terms "Fortean" and "Forteana" are sometimes used to characterize various such phenomena. Fort's books sold ...

, researcher of anomalous phenomena

* '' Chariots of the Gods?'', 1968 book by Erich Von Daniken

* ''Fortean Times

''Fortean Times'' is a British monthly magazine devoted to the anomalous phenomena popularised by Charles Fort. Previously published by John Brown Publishing (from 1991 to 2001), I Feel Good Publishing (2001 to 2005), Dennis Publishing (2005 to 2 ...

''

* Peter Kolosimo

* ''Fingerprints of the Gods

''Fingerprints of the Gods: The Evidence of Earth's Lost Civilization'' is a 1995 pseudoarcheology book by British writer Graham Hancock, which contends that an advanced civilization existed in prehistory, one which served as the common progen ...

'', 1995 book by Graham Hancock

Graham Bruce Hancock (born 2 August 1950) is a British writer who promotes pseudoscientific theories involving ancient civilizations and lost lands. Hancock speculates that an advanced ice age civilization was destroyed in a cataclysm, but t ...

* Vadim Chernobrov

Vadim Alexandrovich Chernobrov (russian: Вади́м Алекса́ндрович Чернобро́в (1965, Volgograd Oblast – 18 May 2017, Moscow) was the founder and leader of the Kosmopoisk organisation. He was a ufology and mystery enthusi ...

, researcher of anomalous phenomena, writer

* Michael Cremo

Michael A. Cremo (born July 15, 1948), also known by his devotional name Drutakarmā dāsa, is an American freelance researcher who describes himself as a Vedic creationist and an "alternative archeologist." He argues that humans have lived ...

, author of several books including ''Forbidden Archeology

''Forbidden Archeology: The Hidden History of the Human Race'' is a 1993 pseudoarchaeological book by Michael A. Cremo and Richard L. Thompson, written in association with the Bhaktivedanta Institute of ISKCON. Cremo states that the book has " ...

'' (1993)

* Charles Berlitz

Charles Frambach Berlitz (November 22, 1913 – December 18, 2003) was an American polyglot, language teacher and writer, known for his language-learning courses and his books on paranormal phenomena.

Life

Berlitz was born in New York City. He w ...

, linguist and writer of anomalous phenomena

* ''The Mysterious Origins of Man

''The Mysterious Origins of Man'' is a pseudoarchaeological television special that originally aired on NBC on February 25, 1996. Hosted by Charlton Heston, the program presents the fringe theory that mankind has lived on the Earth for tens of ...

'', originally aired on NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

in 1996

References

External links

{{Commons category, OOPartsCritical perspective on Creationist and New Age claims related to out-of-place artifacts

at Bad Archaeology

''Archaeology from the dark side''

at

Salon.com

''Salon'' is an American politically progressive/ liberal news and opinion website created in 1995. It publishes articles on U.S. politics, culture, and current events.

Content and coverage

''Salon'' covers a variety of topics, including re ...

Out-of-place artifacts article

at Bad Archaeology Forteana Pseudoarchaeology